| Date of decision: | 28 November 2025 |

| Body: | Australian Patent Office |

| Adjudicator: | Dr S. J. Smith |

Introduction

IP Australia has dismissed Adama Agan Ltd’s (Adama) opposition to the grant of Kumiai Chemical Industry Co., Ltd’s (Kumiai) Australian patent application directed to an industrial process for producing the herbicide pyroxasulfone, with Kumiai’s patent application proceeding to grant in early January 2026.

The decision provides a detailed and instructive analysis of inventive step in the context of chemical process claims, particularly where the individual reaction components are well known but their specific combination addresses a substrate-specific industrial problem. It also reinforces the limited scope of Patents Regulation 5.23 as a mechanism for admitting late-filed evidence.

Background

The application (AU 2020300922) relates to a process for oxidising a sulfide precursor to a sulfone (pyroxasulfone) using hydrogen peroxide in the presence of selected metal catalysts (tungsten, molybdenum or niobium) in a mixed aqueous/organic solvent system.

Pyroxasulfone is a commercially valuable herbicide. The specification states that known oxidation methods for preparing pyroxasulfone, including peracid-based systems, are unsuitable for industrial use due to cost, safety concerns, poor yields, and persistent sulfoxide impurities that are difficult to remove and may adversely affect herbicidal performance. The invention described in the specification relates to a process for producing pyroxasulfone which is claimed to be superior in yield, advantageous for production on an industrial scale and contains substantially no sulfoxide derivative which can cause crop injury and impact the quality of the herbicide.

The claims of the application are directed to a process of producing pyroxasulfone, and a product produced by the process.

Claim 1 is the only independent claim, and reads as follows:

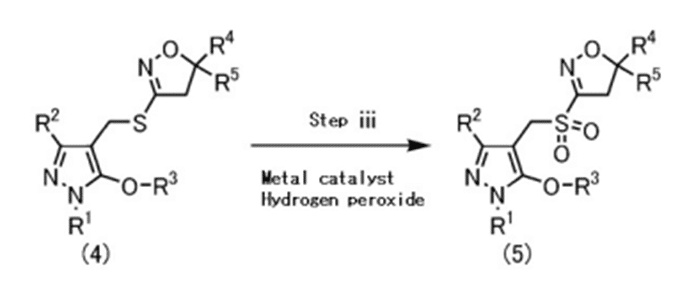

A process for producing a compound of the formula (5), the process comprising the following step iii, wherein the reaction step iii is performed in the presence of organic solvent(s) having an acceptor number of 0 to 50 and a water solvent, wherein the organic solvent for the reaction step iii is one or more organic solvents selected from alcohols, nitriles, carboxylic acid esters and amides: (step iii) a step of reacting a compound of the formula (4) with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a metal catalyst, wherein the metal catalyst is selected from a tungsten catalyst, a molybdenum catalyst and a niobium catalyst, to produce the compound of the formula (5):

wherein in the formula (4) and the formula (5), R1 is methyl, R2 is trifluoromethyl, R3 is difluoromethyl, and R4 and R5 are methyl.

Adama pleaded numerous grounds of opposition initially, however, only the grounds of inventive step and sufficiency were pursued at the hearing. Kumiai had filed post-acceptance amendments narrowing the claims, which were allowed prior to the hearing.

Key Issues

The delegate was required to determine the following issues:

-

- Inventive step

Whether the claimed process would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art in light of the common general knowledge (CGK), given that hydrogen peroxide oxidations, metal catalysts, and aqueous/organic solvent systems were individually well known. - Sufficiency

Whether the specification enabled the skilled person to perform the invention across the full scope of the claims without undue burden. - Procedural issue – Regulation 5.23

Whether late-filed expert evidence submitted by Kumiai should be consulted under Patents Regulation 5.23.

- Inventive step

Consideration

Procedural Issue – Patents Regulation 5.23

Kumiai did not file any evidence in answer to Adama’s evidence within the deadline. Kumiai requested an extension of time but that was refused. Some two months later Kumiai filed evidence. The delegate refused to consult Kumiai’s late-filed evidence, finding that it was essentially evidence in answer filed out of time, that no exceptional circumstances existed, and that admission would unfairly prejudice Adama. Importantly, the delegate concluded that the material was not crucial to resolving the opposition.

Inventive Step

Expert evidence on inventive step was filed by Adama, consisting of a declaration by Professor James Hanley Clark, a Senior Professor at the University of York specialising in green and sustainable chemistry with over 45 years of experience working in the field of chemistry. As noted above, the expert evidence filed by Kumiai, although considered relevant, was not consulted, due to it being filed out of time.

In assessing the CGK, the delegate was satisfied that the relevant CGK included the knowledge that hydrogen peroxide is one of (many) oxidants which may be used to oxidise sulfides to sulfones, optionally in the presence of a metal catalyst, and often in the presence of water and a co-solvent such as acetone or an alcohol. The delegate considered that various suitable metal catalysts, including tungsten-based catalysts, would be known to the skilled person as would various other oxidants and associated conditions.

Professor Clark’s evidence was that, without hindsight, he arrived at a process falling within the scope of the claims, and on this basis Adama submitted that the claims lacked an inventive step in light of the common general knowledge alone. However, the delegate, quoting AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30 at [23] noted that it is important to recall that the notional skilled person is not a reference to a specific person, it is a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining the issue of inventive step. The delegate stated that, as such, evidence of Professor Clark’s approach is not an answer in itself to the question of obviousness. Idiosyncratic knowledge or preferences of a skilled person are relevant to the weight that can be attached to their evidence. While it seemed reasonably clear that the components of the claimed reaction method, individually, were part of the CGK, the question was whether the notional skilled person would be directly led to their use, in combination, with an expectation of achieving an industrially useful process for the preparation of pyroxasulfone. Kumiai identified several difficulties with Professor Clark’s evidence which led the delegate to conclude that overall, the evidence revealed a measure of unpredictability. Added to this, the specification itself revealed a significant difference in efficacy between the Comparative and Reference Examples, despite structural similarities. The delegate did not consider the evidence to support a conclusion that a skilled person could a priori form an expectation that an industrially useful process would be achieved with any particular oxidant (and associated reaction conditions) and substrate combination. The delegate agreed with Kumiai that, while the claimed reaction conditions might be included in an experimental program, this does not equate to an expectation that they will solve the relevant problem, or to a conclusion that they are a combination of conditions, out of many possibilities, to which the skilled person would be “directly led”. On balance, the delegate was not satisfied that it had been established that the notional skilled person, in view of the CGK alone, would, when seeking an industrially useful process for the production of pyroxasulfone, be directly led to the claimed combination of reaction parameters.

Adama also relied on six prior art documents to establish a lack of inventive step. However, the delegate was not satisfied that lack of inventive step in light of any of these documents was made out.

In summary, the delegate emphasised that although each element of the claimed process was known in isolation, the correct question was whether the combination of features would have been arrived at by the skilled person with a reasonable expectation of success, not whether it could be assembled with hindsight.

The key points underpinning the finding of inventiveness included:

- Substrate-specific unpredictability

Oxidation of sulfides to sulfones is highly substrate dependent. The prior art showed that similar reaction conditions could yield sulfoxides, sulfones, or mixtures depending on the substrate. There was no evidence that the skilled person would expect the claimed conditions to successfully and reliably produce pyroxasulfone with low sulfoxide content. - Departure from mainstream industrial practice

The evidence indicated that conventional industrial processes favoured peracid/acetic acid systems, not aqueous hydrogen peroxide systems. The delegate found that the skilled person would not be directly led away from established industrial practice absent a clear reason to do so. - Non-routine selection of parameters

The claimed selection of specific metal catalysts, solvent classes defined by acceptor number, and mixed aqueous/organic systems was not shown to be routine optimisation. Rather, it reflected an inventive selection that rejected other plausible alternatives. - Unexpected technical effect

The specification demonstrated that peroxide-based systems using certain catalysts could stall at the sulfoxide stage, and that the claimed solvent system unexpectedly enabled sufficient oxidation to the sulfone while suppressing impurities. Comparative examples showing failures with closely related compounds were particularly persuasive.

The delegate also cautioned against equating an expert’s personal preferences with the hypothetical skilled person, noting that expert reasoning influenced by specialist interests (such as “green chemistry”) may not reflect mainstream industrial expectations.

Sufficiency

The sufficiency ground was pleaded only in relation to claims 14 – 18 which were dependent product-by-process claims defining the product produced by the process of any one of claims 1- 12, comprising specified low percentages of the sulfoxide derivative.

Adama submitted that it was not plausible that the claims could be worked across their breadth, having regard to the number of variables (such as, reaction conditions, catalysts and solvents) which may be used in the process claimed in claim 1. Kumiai submitted that the examples provided broad support for the claims as they demonstrated a broad range of solvents and each of the metal catalysts, and there was no evidence to suggest that anything within the claims would not work.

The delegate found that Adama failed to establish insufficiency of these claims on the basis that:

- The claims were directed to a narrowly defined substrate.

- The specification contained multiple working examples across the claimed catalyst and solvent classes.

- A skilled person could perform the invention without undue experimentation.

The delegate noted that although not every embodiment within claim 1 achieved the very low sulfoxide impurity thresholds recited in the product-by-process claims, the relevant question was whether those claims could be worked across their full scope without undue burden. Following post-acceptance narrowing of the claims to pyroxasulfone and to specific metal catalysts, the specification was found to provide a sufficient range of examples demonstrating that the claimed impurity levels could be achieved. Any further optimisation of reaction conditions was considered routine experimentation for the skilled person, not an undue burden.

Outcome

The opposition was unsuccessful, with the patent application proceeding to grant in early January 2026. Costs were awarded against Kumiai up to 4 April 2024 (pre-amendment), and against Adama from that date onward, reflecting the delegate’s view that Adama should not have persisted with the opposition after the claims were narrowed.

Implications

For IP Practitioners

- This decision reinforces that chemical process claims remain defensible where inventiveness lies in the selection and combination of known reaction parameters.

- Comparative data showing failures for close analogues is highly influential in defeating obviousness attacks.

- Expert evidence must demonstrate what the skilled person would expect to succeed, not merely what is “worth trying”.

- Patent Regulation 5.23 will be applied narrowly; procedural discipline in opposition evidence remains critical.

- Strategic post-acceptance amendments can materially affect both substantive outcomes and costs exposure.

For Applicants

- Improvements to known manufacturing processes can still attract robust patent protection where they solve real industrial problems such as impurity control, yield, safety, or scalability.

- Even in mature chemistry fields, unpredictable substrate behaviour can support an inventive step finding.

- Well-drafted specifications that explain the technical problem and provide comparative evidence significantly strengthen enforceability.

About Pearce IP

Pearce IP is a specialist firm offering intellectual property specialist lawyers and attorneys with a focus on the life sciences industries. Pearce IP and its leaders are ranked in every notable legal directory for legal, patent and trade mark excellence, including: Chambers & Partners, Legal 500, IAM Patent 1000, IAM Strategy 300, MIP IP Stars, Doyles Guide, WTR 1000, Best Lawyers, WIPR Leaders, 5 Star IP Lawyers, among others.

In 2025, Pearce IP was recognised by Australasian Lawyer and New Zealand Lawyer’s 5 Star Employer of Choice, and is the “Standout Winner” for inclusion and culture for firms with less than 100 employees. Pearce IP was awarded “IP Team of the Year” by Lawyers Weekly at the 2021 Australian Law Awards. Pearce IP is recognised by Managing IP as the only leading ANZ IP firm with a female founder, and is certified by WEConnect International as women owned.

Sally Paterson

Executive, Lawyer (NZ), Patent & Trade Mark Attorney (AU, NZ)

Sally is a senior Trans-Tasman Patent and Trade Mark Attorney, and a New Zealand registered lawyer with over 20 years’ experience in IP. Sally’s particular expertise is in life sciences, drawing from her background in biological sciences. Sally is well respected in the New Zealand IP community for her broad ranging skills in all aspects of intellectual property advice, protection and enforcement. Sally has extensive experience securing registration for patents, designs and trade marks in New Zealand, Australia and internationally, providing strategic infringement, validity and enforceability opinions, acting in contentious disputes including matters before the courts of New Zealand and before IPONZ and IP Australia, and advising on copyright and consumer law matters.

Helen Macpherson

Executive, Lawyer (Head of Litigation –Australia)

Helen is a highly regarded intellectual property specialist and industry leader with more than 25 years’ experience advising on patents, plant breeder’s rights, trade marks, copyright and confidential information. She is known for her expertise in complex, high-value patent matters and leverages her technical background in biochemistry and molecular biology to work across a wide range of technologies, including inorganic, organic, physical and process chemistry, biochemistry, biotechnology (including genetics, molecular biology and virology), and physics. Helen is an active member of the Intellectual Property Committee of the Law Council of Australia and the Intellectual Property Society of Australia and New Zealand.