In the first such judgment since the 1980s, Justice Moshinsky has granted an interlocutory injunction to prevent TMA from threatening patent infringement proceedings against UbiPark’s customers pending judgment on the merits in the litigation. This case, UbiPark Pty Ltd v TMA Capital Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 111, suggests that it will be difficult for a maker of threats to avoid an interlocutory injunction pending judgment, raising difficult questions as to how a patentee can seek to avoid unnecessary litigation by sending correspondence in advance.

Background

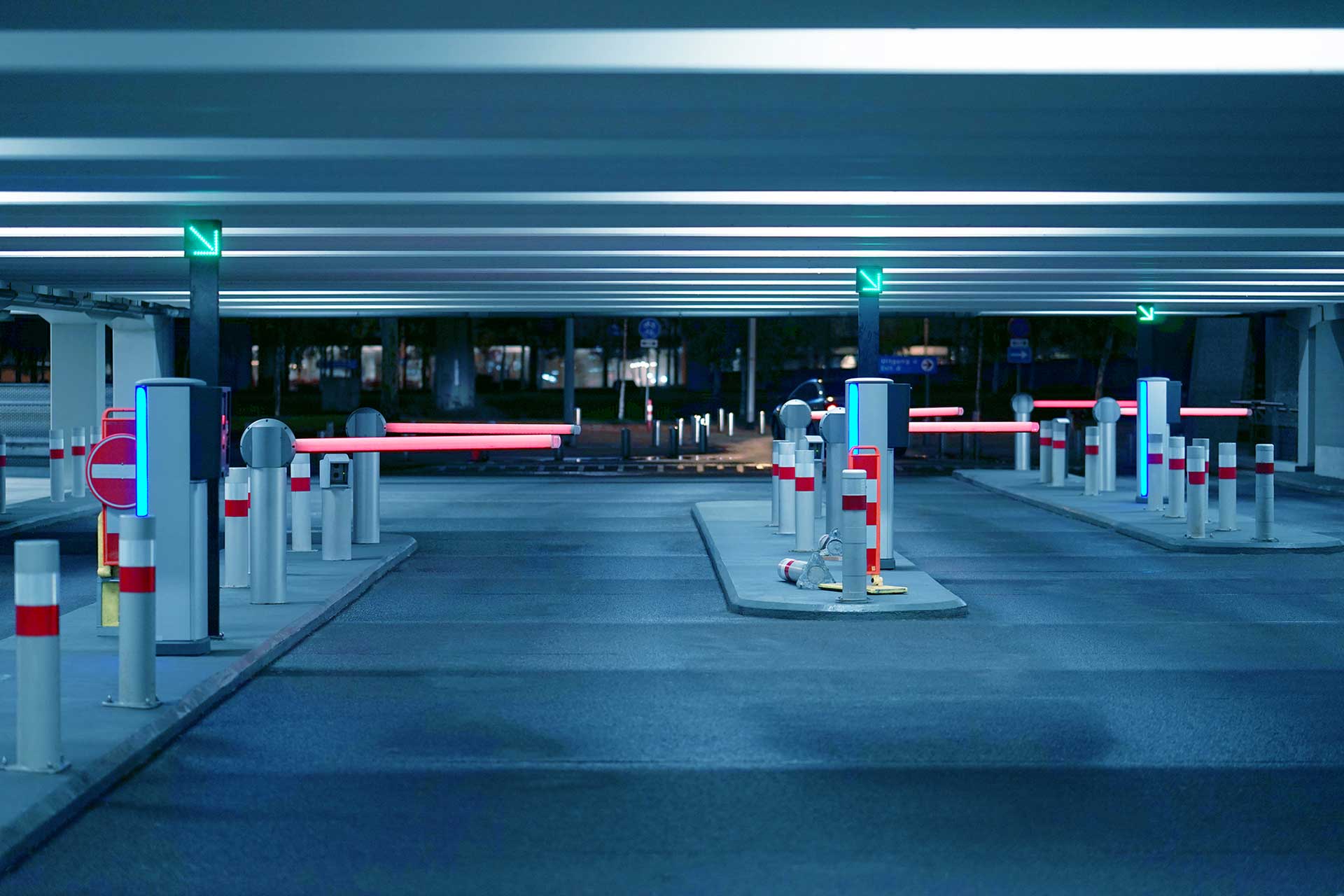

UbiPark and TMA are rival providers of car park access systems. TMA obtained a patent relating to a system, method and computer program for controlling access to a car park. UbiPark provides car park operators with a digital platform that allows drivers to access operators’ car parks using a UbiPark smartphone application.

TMA sent letters of demand to UbiPark and its car park operator customers threatening patent infringement proceedings based on their provision and use of the UbiPark platform respectively.

UbiPark, being a person aggrieved by TMA’s actions, sued TMA for making unjustified threats of patent infringement proceedings. UbiPark sought a declaration that the threats (which TMA admitted were threats) were unjustified, a final injunction to restrain TMA from making further threats pending patent expiry, and an interlocutory injunction to restrain TMA from making further threats pending judgment. TMA subsequently filed a cross-claim against UbiPark for infringement of the patent and UbiPark responded by alleging invalidity of the patent.

For the purpose of the interlocutory injunction application only, the parties agreed to assume that that the patent was valid and that claim 1 alone was alleged to be infringed.

Two-stage test

Moshinsky J observed that there only appeared to have been two cases, both from the 1980s, in which an interlocutory injunction had been sought to restrain unjustified threats of patent infringement proceedings. His Honour went on to apply the usual two-stage test in interlocutory injunction applications:

- first, whether UbiPark had shown a prima facie case that TMA’s threats were unjustified; and

- second, whether the balance of convenience favoured the grant of an injunction.

This involved a reversal of the usual onus of proof in interlocutory injunction applications in patent cases, as it is usually the party alleging patent infringement that must meet the relatively low threshold of showing a prima facie case of infringement.

Prima facie case

Except in the case of one of UbiPark’s platform configurations, UbiPark argued that it did not infringe claim 1 because two claim elements were not present in its platform, relying on evidence from its Chief Technology Officer. TMA countered with evidence from an independent expert, whose technical views, together with his interpretation of the two claim elements, led him to conclude that the claim was infringed. His Honour’s view was that the disputed issues were largely issues of claim construction, and that either party could succeed at trial. UbiPark had therefore shown a prima facie case that TMA’s threats were unjustified.

Interestingly, TMA did not appear to argue that its threats of patent infringement proceedings would have been justified even if the patent was subsequently found to be invalid and/or not infringed (on the basis that TMA had an arguable case of infringement and in that sense, did not make the threats in an ‘unjustifiable’ fashion). Such an argument may have been open to TMA following Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 568 and Damorgold Pty Ltd v Blindware Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1552, although there is authority to the contrary in the form of CQMS Pty Ltd v Bradken Resources Pty Ltd (2016) 120 IPR 44.

Balance of convenience

In addressing the second part of the test, Moshinsky J first explained that an interlocutory injunction would not preclude TMA from notifying UbiPark’s operator customers of the existence of the patent or of the fact that the litigation was on foot. Nor would it prevent TMA from suing for patent infringement. The injunction would only prevent TMA from making further threats of patent infringement proceedings to UbiPark’s operator customers.

His Honour considered that the balance of convenience favoured granting an interlocutory injunction. UbiPark would likely suffer harm if further threats were made pending judgment in the case, for example, the loss of existing and potential customers, and a damages award might not provide adequate compensation, for example, due to difficulties of proof and quantification. In contrast, TMA was less likely to suffer harm if it was unable to make further threats pending judgment, including because TMA would still be able to notify UbiPark’s operator customers of the existence of the patent and the litigation. Granting an injunction would also preserve the status quo in a practical sense.

Therefore, as both parts of the test were satisfied, an interlocutory injunction was granted.

Genuine steps

Moshinsky J noted that, if TMA wanted to sue any of UbiPark’s operator customers, it would ordinarily be required to specify the ‘genuine steps’ that had been taken to try to resolve the issues in dispute without resorting to litigation. The question was, how could TMA take genuine steps if it was enjoined from sending any communications that could constitute a threat of patent infringement proceedings? His Honour did not address that question because he considered the prospects of TMA suing UbiPark’s operator customers (being potential customers of TMA) were remote. Detailed consideration was given to this issue in CQMS v Bradken, in which Justice Dowsett characterised each of the patentee’s communications as either an actionable threat or a genuine attempt to resolve the dispute that did not amount to a threat. However, the original letter of demand in that case was characterised as a threat, suggesting that taking genuine steps to resolve the issues in dispute while not making an unjustified threat of patent infringement proceedings is akin to walking a tightrope.

Implications

This case suggests that, where a claim of unjustified threats of patent infringement proceedings is made, it could be difficult for the maker of the threats to avoid an interlocutory injunction to restrain them from making any further threats pending judgment in the case. The person aggrieved by the threats would typically be able to meet the low threshold of showing a prima facie case, and the balance of convenience is likely to tip in their favour. Patentees should be mindful of this potential consequence when sending pre-litigation correspondence.

Naomi Pearce

CEO, Executive Lawyer (AU, NZ), Patent Attorney (AU, NZ) & Trade Mark Attorney (AU)

Naomi is the founder of Pearce IP, and is one of Australia’s leading IP practitioners. Naomi is a market leading, strategic, commercially astute, patent lawyer, patent attorney and trade mark attorney, with over 25 years’ experience, and a background in molecular biology/biochemistry. Ranked in virtually every notable legal directory, highly regarded by peers and clients, with a background in molecular biology, Naomi is renown for her successful and elegant IP/legal strategies.

Among other awards, Naomi is ranked in Chambers, IAM Patent 1000, IAM Strategy 300, is a MIP “Patent Star”, and is recognised as a WIPR Leader for patents and trade marks. Naomi is the 2023 Lawyers Weekly “IP Partner of the Year”, the 2022 Lexology client choice award recipient for Life Sciences, the 2022 Asia Pacific Women in Business Law “Patent Lawyer of the Year” and the 2021 Lawyers Weekly Women in Law SME “Partner of the Year”. Naomi is the founder of Pearce IP, which commenced in 2017 and won 2021 “IP Team of the Year” at the Australian Law Awards.